Kill Your Heroes

Believe in Ideas, Not People

Well, it is finally here.

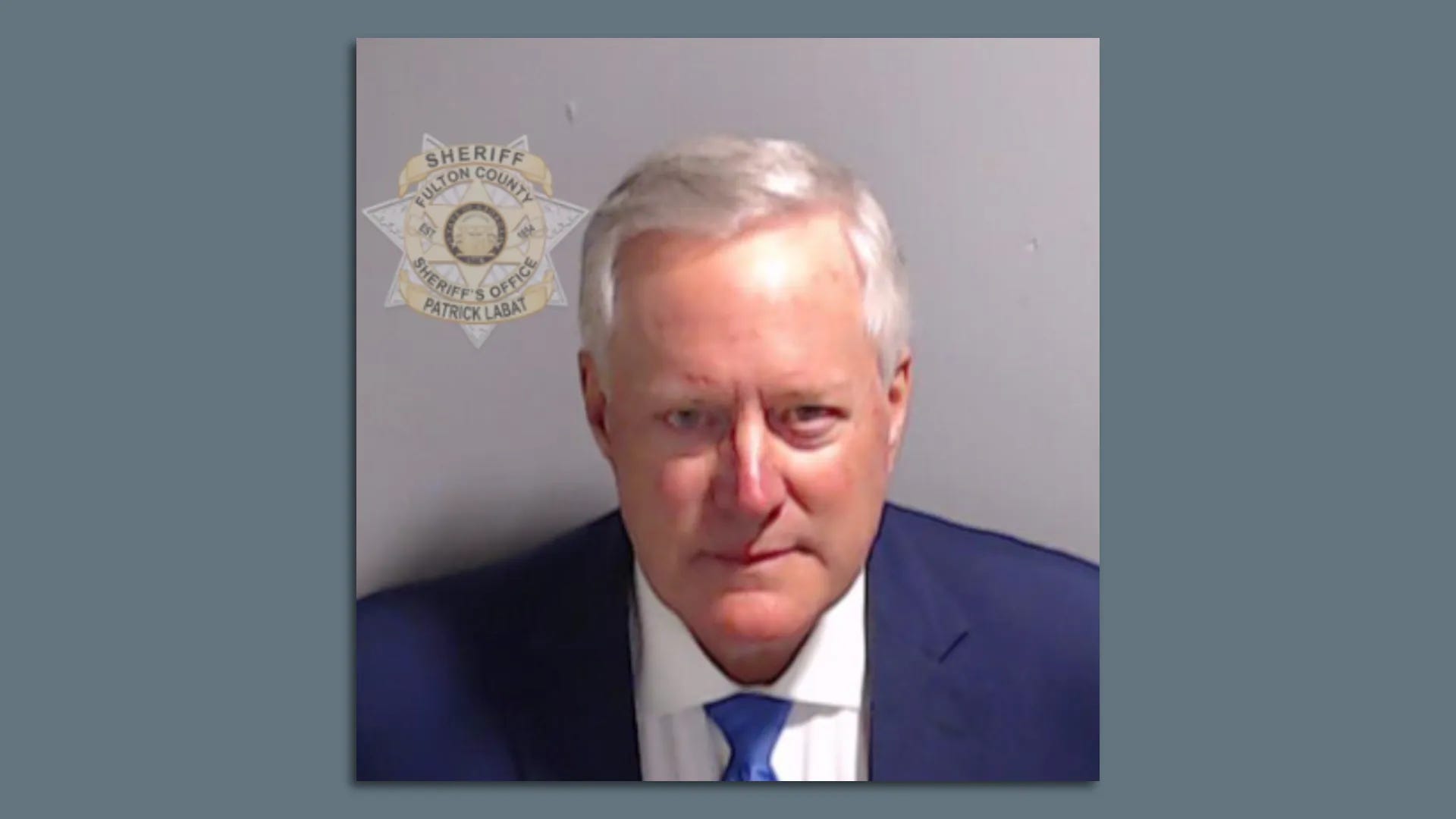

The photo I knew I would eventually see once the news broke, in April of 2023, that a man I had once considered on of my biggest intellectual heroes was implicated in the greatest political scandal of the 21st Century: the Epstein Affair.

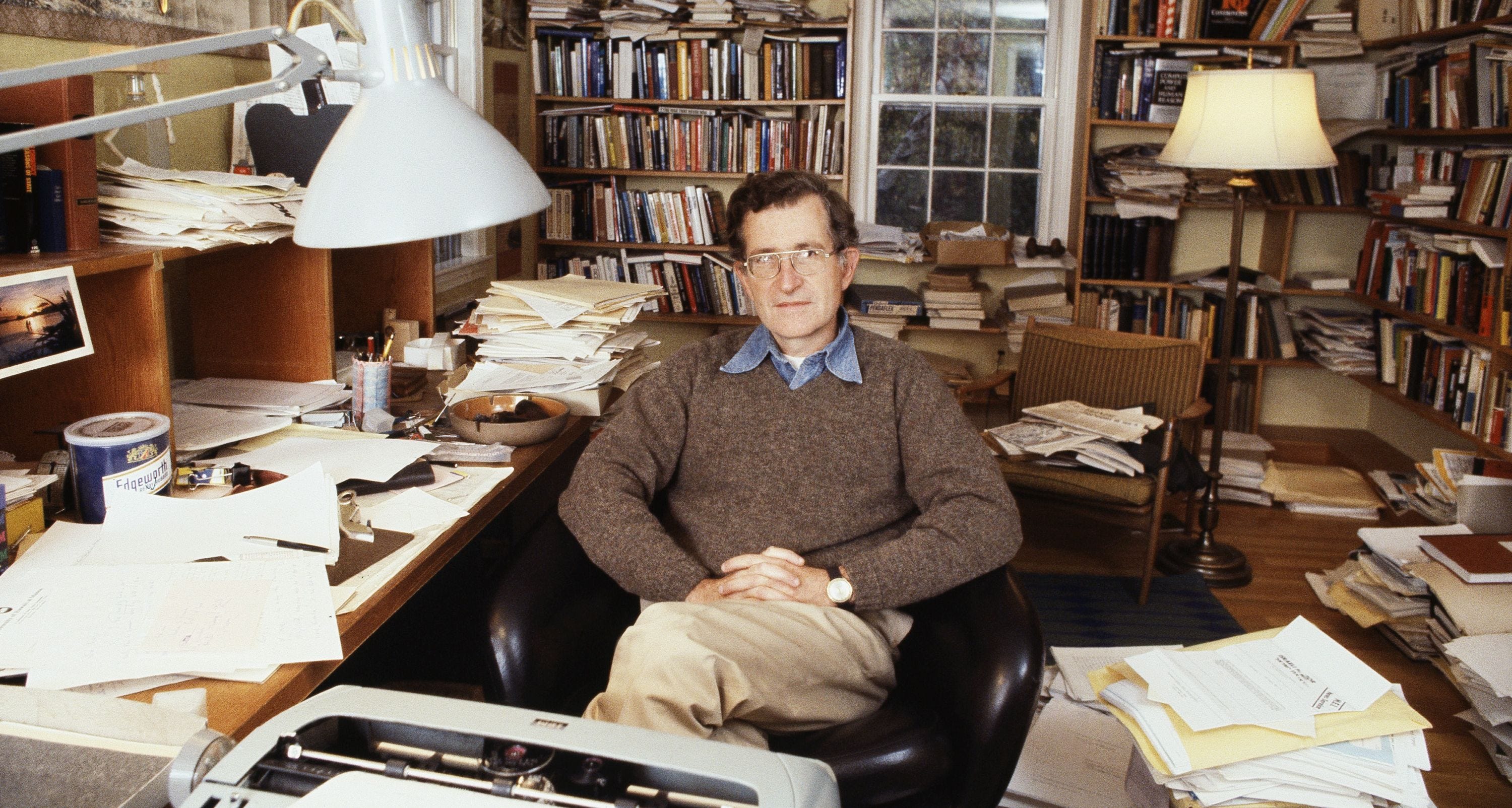

If you are subscribed to this newsletter and don’t know who Noam Chomsky is, I would be shocked.

For half a century, Chomsky has been at the forefront of the Western intellectual counterculture. A rigorous and disciplined academic, Chomsky dedicated his career to unmasking the wheels of American empire, and showing the true face of its savagery to the world.

A linguist by training, Chomsky rose to fame as something of a political philosopher and cultural critic. His books and articles criticizing everything from the American-sponsored genocide in East Timor to the web of political entanglement that has trapped the Palestinians in a perpetual battle for survival and visibility.

Reagan, Carter, Nixon, Bush Sr. and Jr., Clinton, Obama, Trump. Chomsky was ruthless in his criticism of each one, pulling on the thread of unquestioned American imperial arrogance that defined each of their administrations.

On the subject of Israel, he shed critical light on the abuses carried out in the name of Jews and under the guise of protecting them by that state. As a Jew himself, Chomsky was well-positioned to criticize Zionism and still find that some people were willing to listen.

His 1988 book Manufacturing Consent became one of the seminal texts in media theory, assigned in academic courses worldwide, and still in print to this day.

Given Chomsky’s recent association with Epstein, the book’s title takes on a whole new meaning.

False Messiahs and Empty Idols

I have written extensively about my own journey out of the Far Right, Christian Evangelical subculture that defined my youth and into what I would describe as an anti-authoritarian, democratic absolutist political identity.

That journey had many stages. The first involved leaving behind the politics of the Christian Identity movement and entering a kind of Centrist milieu that took on an increasingly progressive, Social Democratic character throughout my early to mid-Twenties.

The next stage involved leaving behind Democratic Party politics altogether after understanding the degree to which the Democratic and Republican parties both serve the interests of the ruling class.

At each stage, I had to make a gradual, but definite break with the idols that defined each of these factions. The first idol I had to smash was the notion that the United States was a Christian nation that played a special role in the world as a kind of physical bulwark of Christendom.

America was special, you see. And God would somehow use its uniqueness to bring about the Kingdom of Heaven. How exactly was a matter of debate among the Evangelical Right, but everyone agreed on the proposition–more Mormon in its implications than Christian–that America had a part to play in the Eschaton.

This idol was easily smashed when I realized freshman year of college what a historically idiotic proposition this was. American Exceptionalism, Manifest Destiny, and Christian Nationalism went out the window with my childhood Neo-Confederate worldview and the dizzying Creationist belief that the earth was 6,000 years old.

Severing ties with the community that grants you access to power and resources always has consequences. And while I maintained ties with many from my previous circles, I began the process of making a clean break with this world following the election of Donald Trump.

Watching people I had grown up respecting bend the knee to a fascist pedophile seemed like the opposite of the Christ-centric, limited government “Constitutional Conservatism” to which everyone I grew up with claimed to adhere.

My childhood debate coach now has a mug shot in Fulton County, GA for trying to steal a federal election.

My Bible-thumping, Traditional Marriage, Pro-Life, Freedom Caucus-member Congressman, for whom I spent weeks of my life phone banking and stumping, fucked a fossil fuel lobbyist. His poor wife at least had the dignity to leave him. His Evangelical Christian staff members stayed.

The guy who wrote my homeschool history curriculum–more a Calvinist theonomic polemicist than anything resembling an actual historian–now appears on Red Pill podcasts spewing Christofascist nonsense and running cover for the witless pedophile currently serving as our President.

Those idols were easier to smash. Those heroes were easier to kill.

The ones that were more difficult to detach from were those that I clung to as I was lifted out of the cesspool of movement Conservatism and its ascendant fascist wing.

I’m A New Deal Democrat

Figures like Robert Reich, Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, Anand Giridharadas, and Pierre Bourdieu delivered me from the Centrist stew in which I found myself after forsaking the suffocating bosom of Evangelical Christofascism.

They offered a sort of alluringly optimistic Social Democratic vision derived from New Deal liberalism, postwar Keynesianism, legal reformism, and moral critiques of inequality.

Their perspective could be adequately summed up in Bill Clinton’s famous (and oft-repeated) slogan:

“There is nothing wrong with America that cannot be cured by what is right with America.”

Taken together, these figures offered me a chance to save my beloved America from all its monumental sins. If we could just get back to a New Deal style of socialized, economic populism, we could redeem the American Experiment as a whole. It wasn’t the train that was broken, but the conductors. With a little tinkering, we could get the whole thing back on track.

In this imagining, America was still a shining City on a Hill, but one that stood for fairness, huddled masses, and optimistic chutzpah, rather than Manifest Destiny, capitalist excess, and Christian domination.

These heroes did not exactly let me down. More accurately, they served as stepping stones from Liberalism to the proper Left.

I would ultimately move past their particular brand of finger-wagging Left-Liberalism and into full blown skepticism of the origins, structure, and purpose of our American leviathan.

This was another chasm that I gradually leaped, but the man who did the most to bridge this gap was none other than Noam Chomsky.

You’ve Come to the Wrong Shop for Anarchy, Brother

I think the moment I called myself an Anarchist for the first time was on a beach in somewhere in Costa Rica in early 2021. I was reading The Washington Connection and Third World Fascism, a lesser known work of Chomsky’s, but the one that left the biggest impact on me.

As I have pointed out before, I do not make a particularly natural anarchist.

I guess I just made a close observation of the way power works, started reading widely and deeply, and kept being surprised that the people I agreed with the most tended to describe themselves as Anarchists.

I had already read Chomsky’s essay On Anarchy before that Costa Rican beach. I had found it interesting and enlightening, if not exactly compelling. But thumbing through the concluding pages of The Washington Connection, I emerged with a picture of the way that America acts in the world that was, essentially, wholly irredeemable.

Once more I had to reconstruct my political identity in the wake of a shift in perspective that had been gradual, but definite. Over the next few years, I would arrive at the composite worldview that I have shared with you all over the course of my writing on Substack.

It is an outlook that I believe is optimistic, but not delusional. One skeptical of power and those who seek it. Skeptical of borders, cops, and systems designed to extract and distract. Wary of the Leviathan state and its disregard for the individual. Wary of capitalism and its elevation of the individual beyond the community.

It is neither Marxist, nor animist, nor Christian, nor Libertarian, nor even strictly Anarchist. But rather an amalgam of many traditions, lay and intellectual.

It is an outlook derived from having believed and acted upon a great many stupid ideas, steeped in the humility of growing things, and united by a hope beyond despair that all might yet be made right.

If we can learn to kill our heroes before they let us down, we can build a worldview that does not depend on the personal integrity of the people whose ideas we respect.

Intellectually, I owe a great debt to figures like Noam Chomsky, but I haven’t idolized him for a long time. The cracks in my idol started to form when I looked into his inconsistent record on genocide and human rights issues, from the Balkans to Cambodia and Ukraine.

I realized that even this man who got it so right so often could still get it badly wrong on occasion. So I smashed that idol too. I took the ideas that had merit, and took the man who popularized them off his pedestal.

Accordingly, when the news of Chomsky’s connection to Epstein dropped two years ago, it felt less like a radical confrontation to my worldview, and more like a pang of regret for a figure I had, at one time, endowed with a great deal of respect.

Heroes Can’t Let You Down If They’re Dead

I remember my freshman year of college I heard a speech delivered by a young man of great eloquence and principle whom I still consider a close friend. In fact, I just received his Christmas card in the mail.

The speech was entitled Kill Your Heroes and it was his final address to our little gathering of young men who imagined themselves inheritors to the tradition both of principle and of eloquence.

In the speech, he grappled with his idolization of Martin Luther King Jr. as a young man, only to discover that King was a serial adulterer, a man–a Reverend, shepherd of a flock that looked up to him–who deceived his wife and repeatedly violated her trust.

The notion that I could mean something as a man or as a symbol beyond my own internal experience of insecurity, self-doubt, and constant uncertainty seemed wholly foreign.

The principle that he derived from this experience was that our heroes will always let us down, and what matters is less how we react to that and more what we learn from it. If we cannot separate the ideas we admire from the people who espouse them, we risk losing the one when the other fails us.

I have adopted this outlook as a matter of course, and by virtue of experience. I’ve had a lot of heroes let me down. All men are flawed, some more severely than others. But if we can learn to kill our heroes before they let us down, we can build a worldview that does not depend on the personal integrity of the people whose ideas we respect.

We do this by smashing those idols in our heads before they disappoint us.

The Mahdi Is Too Humble To Call Himself The Mahdi!

I’ll conclude this reflection on a personal note. I frequently get messages from people who tell me that something I have written, said, or done meant a great deal to them.

Husbands who read my newsletter to their wives when they were going through a period of loss and hopelessness.

Young men pulled back from the precipice of misogyny and the alt-right pipeline by seeing a strange kind of compassionate masculinity modeled for them by, well, me.

Old heads made cynical by time and experience, taking courage and hope from my words.

Palestinian or Ukrainian international students grateful that the plight of their people is being spoken about by a white American man to a large audience from deep within the imperial core.

All of these messages are quite sincere, and some of them are truly very flattering. But I occasionally get the nagging feeling that they can, at times, smack of hero worship.

I think that when certain people see the way I move in the world, the social, professional, and physical risks I take for the things I believe, and the way that I try to temper my zealotry with compassion and empathy, certain people can find it compelling.

Every time a disaster strikes or war kicks off somewhere in the world, I get a flood of messages from people asking me when I’m dropping into the crisis zone. One even joked that I am like the “Forrest Gump of global catastrophe,” after I arrived back home from war-stricken Lebanon and was inside the UCLA Palestine encampment within 24 hours.

The trajectory of your personal, political, and intellectual development should be littered with the corpses of False Messiahs.

This amused me for a while, because my neurodivergent brain,1 trained on years of doctrinally reinforced Calvinist self-loathing, has had me convinced my entire life that I am some kind of incurable crash out with a fundamental flaw or evil at the very center of my being.

The idea that people could look at me as anything other than how I look at myself perplexed me. The notion that I could mean something as a man or as a symbol beyond my own internal experience of insecurity, self-doubt, and constant uncertainty seemed wholly foreign.

Particularly since I was receiving the kind of negative feedback to my public activism that I would expect from the people I grew up with in the Evangelical Right, as well as the Professional Managerial Class of advice-givers concerned that my tendency to rock the boat did not make for a particularly sound career strategy.

But now, the negative feedback is rarer and less personal. Humorously, even many longtime critics have been muted or won over by watching me throw my Bagginsmaxing-ass into situation after situation and come out on the other side with my empathy and moral compass somehow intact.

What I experience now–aside from the occasional death threats from Nazis and Zionists–is really a steady stream positive feedback that is often freighted with flattering statements about my character, courage, and eloquence.

These are things that really matter to me. They are the things I want to be complimented on, more than success or looks or taste or whatever.

And therein lies the danger.

Pride Cometh Before The Fall

One of those early Calvinist imprints that never left me was a story my Dad told me of how the first phrase children raised in Puritan New England would learn was “Abominate pride.”

Setting aside the humorous image of a toddler trying to pronounce the word “abominate,” the Puritans seemed to understand something about humility that they thought was desperately important to communicate to even the youngest of children. Pride cometh before the fall.

How many idols have we had to smash over the years who achieved the heights of renown and influence, only to crash just as hard, thinking they were untouchable?

I suppose what I am saying, as far as all this relates to me, is that I am going to disappoint you. I am going to let you down. If I am doing my job correctly, you will outgrow me. You will move past the place where I stopped, and look back and see me in the same imperfect light that I see myself.

Obviously, I won’t be caught up in an Israeli-backed elite human trafficking scandal (inshallah), but I will find other ways to disappoint you. Or if not disappoint, then certainly give you cause to remove me from any sort of exemplary pedestal you might have placed me on.

I am going to let you down. If I am doing my job correctly, you will outgrow me.

This might all sound very dramatic and stoic, because, well, it is.

In the proper sense of that word, using as its referent the Roman stoic philosophers, who constantly placed internal checks on their own ambition before they had cause to do so.

They understood that humility was a virtue precisely because it protects you from the trap of overweening arrogance before the inevitable fall from grace.

Look, if I can model a way of living, thinking, and moving in the world that you find admirable, that’s great, but I would caution you against believing that it is anything unique about my character that you admire, rather than the ideas and experiences that have influenced it.

These ideas and experiences are available to you as well, and in seizing them, you will quickly move past all the heroes you have elevated to a place in your mind that you have convinced yourself is inaccessible.

The trajectory of your personal, political, and intellectual development should be littered with the corpses of False Messiahs. This is the only way to become a fully formed human being, confident in your words and deeds, and assured that your moral compass still points true North.

I hope to send you all another message before Christmas, but if I crash out or get lazy and forget to do so, Merry Christmas!

The Winter Solstice is upon us!

We’re already halfway out of the dark.

People with AdHD often have a comorbidity called Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria that makes them take even light criticism way to deeply, resulting in a felt sense of personal moral, social, and professional inferiority and brokenness. I have struggled with this all my life, as have several close friends of mine. If you have AdHD or struggle with an irrationally poor self-image, I highly recommend researching RSD and its symptoms.

Seeing a photo of Noam Chomsky with a pedophile and blackmailer is actually not all that surprising.

First, it was his modus operandi to talk to anyone. Second, both probably were incentivized to form a weird relationship with each other. Epstein (an intelligence agent) probably wanted dirt on Chomsky, or to try to control opposition. Chomsky probably wanted to learn about the global elite, and get connected to powerful people (like the prime minister of Israel, who Epstein helped him meet). Perhaps they both wanted to change and teach and shift the other’s perspective and ideology.

Noam Chomsky is 97 years old and can no longer defend himself. He has been viciously attacked his whole life. He has meant so much to so many people across the world. I’m not saying I worship him as a hero, but I’m also not willing to throw the baby out with the bath water.

All of his analysis and interpretation of history and power dynamics are basically correct. It remains a good starting point or place of reference for anyone willing to learn about the world, in my opinion.

well... "when you meet the Hero, kill the Hero"

(it´s kind of tragic, but someone has to do it!) ࿈