Poor, Indebted, Discontented, and Armed

The Unreliability of the White Proletariat

To mark this incredible threshold of 100 paying subscribers, I’m excited to announce that I will be experimenting with a new subscriber benefit. Book club! We will select a book every month and meet together via video call to discuss it. This is experimental, so please indicate your interest in the Subscriber chat here on Substack (not through DM’s) to register your interest. I will send a Calendar invite out soon! Thanks for making my writing possible.

During the height of Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676, the Royal Governor William Berkeley, then in his seventies, penned a letter describing the volatile state of the Virginia colony.

“How miserable that man is that governs a people where six parts of seven at least are Poor, Indebted, Discontented, and Armed?”

Berkeley was one of a great many conservative institutionalists who had the unhappy duty of reining in the settler terrorists of the New World. These were desperate men who were eager to accelerate the sluggish genocide that was quietly sanctioned and largely ignored by the European powers that benefitted from it. That was, after all, the primary thrust of Bacon’s Rebellion, which like most American rebellions, was largely about opposing one authority while imposing another.

The historical passion of the poor, white American for oppressing the poor, black American was rarely exceeded save for his enthusiasm for slaying the indigenous American.

But it was not always this way. This was not a natural state of affairs derived from the meeting of different peoples in the New World, but one that was deliberately imposed, first through force, then through incentive, and nearly always for economic reasons.

The men who led the early American colonists quickly realized that the mixture of races that formed the colonies needed an admixture of racism to make it work for them.

The unreliability of poor, indebted, armed whites has plagued the American ruling class since before it was even American.

Slaves reliably hated slavery. Poor whites rather unreliably hated slaves. Natives were willing to make common cause with both, if it suited their interests. This was an untenable situation for the ultra-wealthy minority that governed the colonies, themselves but the errand boys of European imperialists.

As the American colonial experiment rounded out its first century, there remained a lurking fear in the minds of landed white gentry that, should poor white and poor black make common cause, it would quickly spell the end of their fragile rule. Worse still, if these “poor, indebted, discontented, and armed” threw in their lot with the indigenous nations, it would mean not only the end of their own private fortunes, but the end of colonial rule entirely.

And so they were pitted against one another. Poor white against poor Black. Both against native.

The wealthy white rulers of the Carolinas grew aware of the need for a conscious policy of separation, what became known as “Divide and Rule.” As Governor James Glen of South Carolina wrote in 1755, it was in the interests of the white minority to “make Indians and Negroes a check upon each other, lest by vastly superior numbers we should be crushed by one or another.”

Black slave militias were formed to accompany white militias on Indian raids, meanwhile punishments for Blacks grew steeper than those for white servants for the same offenses.

This was mirrored by an implicit policy that certain poor whites should be elevated to freeholders, given stake in the growing colonial economy, and used as a check on the frontier of Indian territory. This had the effect of softening the hard edges of class that actually governed colonial life, and giving the aspirational white American the impression that his cause was linked with that of the wealthy landholder, rather than the unluckily enslaved Black or indentured White.

Mercifully, American society has moved on from such a preposterous illusion.

Incomplete Revolutions

When Revolution finally did come to America, it arrived within different factions for different reasons. Settlers were upset that the British government denied their demands to expand further into Indian territory beyond the Appalachian Mountains. For their part, the “Indians” mostly sided with the British, and for the same reason they had sided with the French a decade before: because anything was preferable to the insatiable lust of the colonial settlers for Indian land and blood.

Those settlers were themselves the victims both of British colonial repression and economic exploitation by their own elites. Many of them saw the latter as representing a worse kind of oppression than the former.

In my native South Carolina, the Revolution was a bona fide civil war between loyalist Scots-Irish in the Carolina backcountry and landed Patriot merchants on the coast. As a result, more people died in South Carolina in 1777 than in every other theater of the war combined.

It seems a feature, rather than a bug, of American history that disaffected, poor, armed whites are a faction that is highly useful to elite interests but also extremely volatile.

Enslaved Blacks were offered freedom if they would abandon their masters and flee to British lines. Wealthy Boston merchants resented being tyrannized by far-off colonial Lords. They wished instead to exert their own private tyrannies over their holdings.

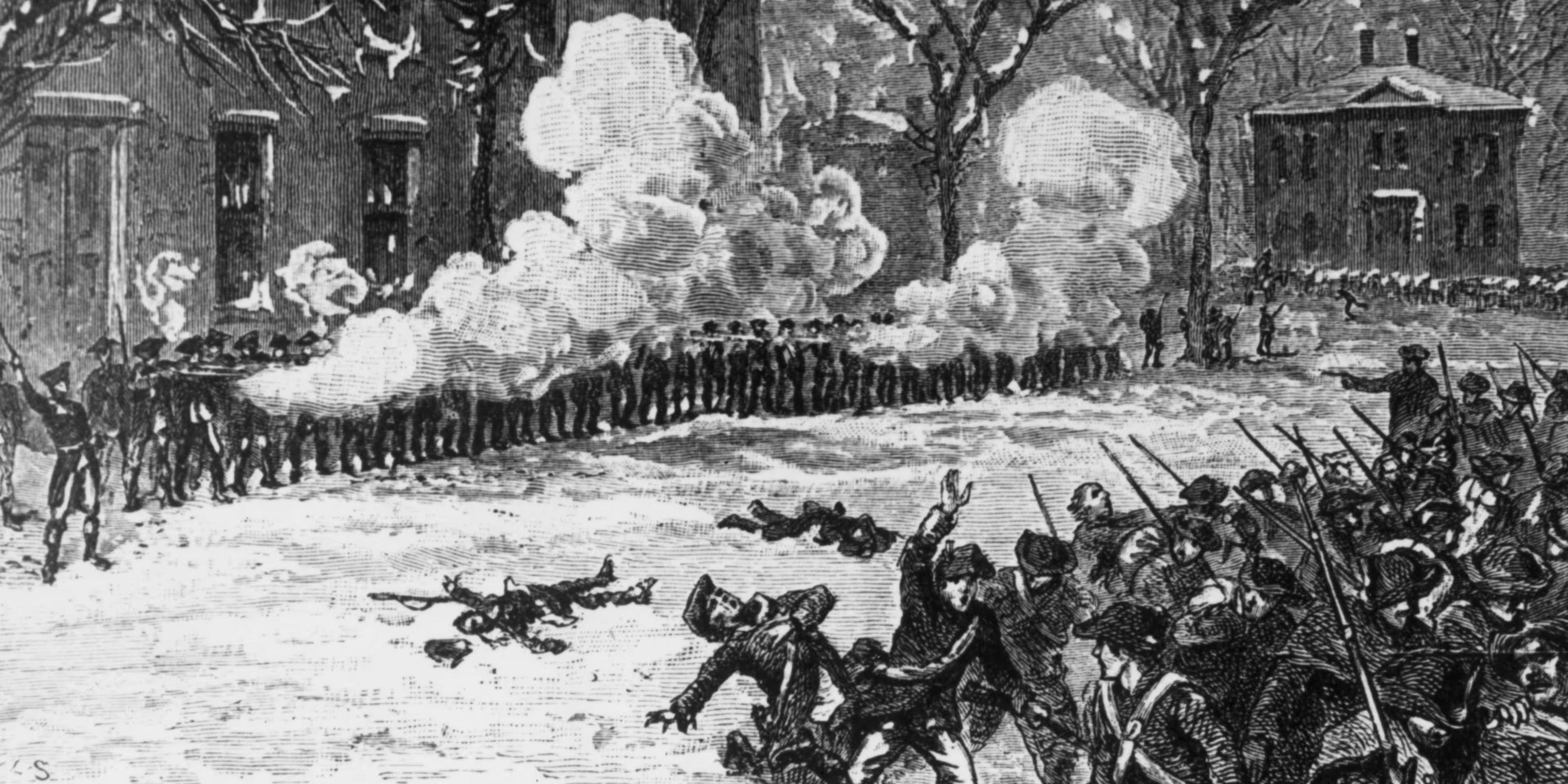

It was these who garnered the most resentment from indebted veterans of the Revolution once American independence was won on the battlefield. Within a decade of victory, a massive popular uprising in Massachusetts that became known–rather inaccurately–as Shay’s Rebellion struck fear into the hearts of the new colonial elite.

This uprising consisted of the same poor, indebted, discontented, and armed whites that had long proved such unreliable allies to the British colonizers. And now they were well-trained veterans, fresh off an unlikely victory against those same colonizers.

But unlike the elite Revolutionaries, they were not inspired by high ideals of political Liberty but by economic realities of political servitude. They pointed out the obvious inconsistencies of how “liberty and justice for all” was applied across class lines. They demanded economic compensation for their wartime service, an end to foreclosures, and to the policy of throwing veterans who could not pay the steep fines into debtors prison.

The local militias were too sympathetic to the rebels to be employed effectively against them, so the Boston elites did what all elites do in similar times of crisis: hired a private army to protect their interests.

In a letter to George Washington in October 1786, General Henry Knox wrote that:

“The people who are the insurgents have never paid any or but very little taxes. But they see the weakness of government. The feel at once their own poverty compared to the opulent, and their own force, and they are determined to make use of the latter in order to remedy the former. Their creed is that the property of the United States has been protected from the confiscations of Britain by the join exertions of all, and therefore ought to be the common property of all. And he that attempts opposition to this creed is an enemy of equity and justice and ought to be swept from off the face of the earth.”

The rebellion disbanded with minimal consequences due to the legitimate grievances of its instigators, and the reluctance of the elites to spark a full-on confrontation that could enable the revolutionary fervor to spread any further.

But the elites learned two important lessons from the rebellion. The first was that the Articles of Confederation were generally too weak to protect the elite from the armed poor. The second was that a strong central government was needed to provide a “check” on popular uprisings that threatened the newly established political order.

And so, at the 1787 Constitutional Convention, a centralized, federated system was formed on American soil with a more powerful executive than any that had ruled the Colonies since the time of Queen Anne.

For all the Revolution’s talk of opposition to the tyranny of King and Parliament, it ended up creating more powerful versions of both.1

From Red Coats to Red Necks

The unreliability of poor, indebted, armed whites has plagued the American ruling class since before it was even American.

While they were employed to great effect in the cause of the Manifest Destiny, the sedition of the Confederacy, and the enforcement of Jim Crow, they had a tendency to act out in unpredictable ways.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Refuse Dystopia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.